I’m Giles Tanner, I’m the general manager of the ACMA’s spectrum team, and next month I am going to step down from my role, which is probably best summed up as being like the town planner of the radiofrequency spectrum.

I kind of stumbled on spectrum work mid-career and coming from a slightly unusual direction—broadcasting regulation. As it happens, this gave me a ringside seat on the largest piece of micro-economic reform attempted, and carried off, in the spectrum field to date, which was Australia’s digital dividend from the closure of analogue TV.

As this is my last speech to you in my ACMA role, I thought I’d share with you a few things I learned from the digital dividend, and what, if anything, it has to tell us about the future. I’ll also like to close with a message for the ‘spectrum natives’. For the record, the opinions expressed will be all my own.

The digital dividend

The government’s part of yielding the digital dividend was completed in April 2017, with the sale, for an eye-watering $1.55bn, of the ‘residual lots’—the three lots of 5 MHz ‘paired’ of wireless broadband spectrum left unsold after the 2013 digital dividend auction. The journey began way back in 1993, with the establishment of a joint working party of engineers from the television industry and the relevant federal communications regulator at the time, the Australian Broadcasting Authority (ABA).

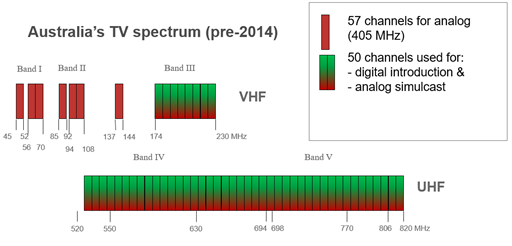

Back in those days, free-to-air television was using mid-20th century technology that required around 405 MHz VHF and UHF spectrum to transmit only five standard definition analog television services to most Australians.

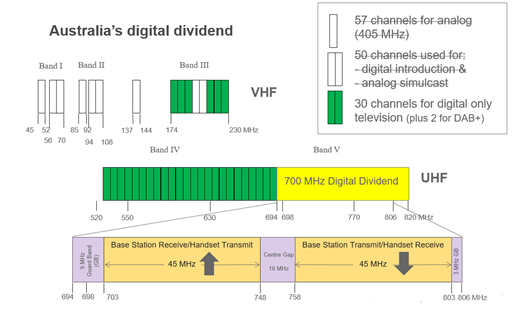

The superior efficiency of first generation digital television technology meant that by 2015, the industry had halved its radiofrequency spectrum requirements, while transmitting 17 television services in all areas (with some of those 17 services in high definition).

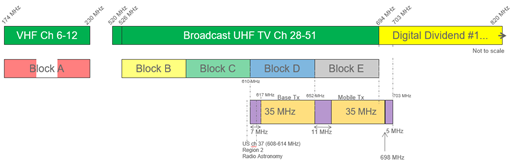

The ‘six channel block’ configuration we have adopted for terrestrial TV services makes the most efficient possible use of the remaining broadcasting services bands and offers long-term advantages for viewers (who require only one simple antenna for all services) and potentially broadcasters (whose identical coverage areas may assist with future innovation of the free-to-air television platform). From the surrendered spectrum, Australia was able to allocate spectrum licences for broadband wireless in the 700 MHz band aligned with the influential Asia-Pacific Telecommunity (APT) 700 MHz plan, providing more ‘waterfront’ spectrum below 1 GHz for growth of wireless broadband than the US or European alternatives.

To give a sense of the size of this task, Professor Jock Given in 2018 estimated that the government outlaid a total of $2.4bn over the life of the project and obtained revenue in return of $3.7bn. These sums do not include the huge, cumulative cost of conversion to Australia’s eight million or so households, nor the additional money spent by the commercial TV industry itself on digitisation. You might imagine that a project on this scale was proceeded by some rigorous cost-benefit analysis, but you would be wrong—indeed, to quote Jock Given again, ‘Australia’s experience of digital switchover showed how a large spectrum re-farming project can be planned and completed despite contested and shifting ideas about the purpose of the whole project’.

Australia's approach to the digital dividend developed in three discernible phases over an approximately 20-year period.

Phase 1 (1993–2000) was exclusively concerned with digitisation of the analogue television service. It was driven by television industry requirements and made detailed provision for the ‘simulcasting’ of analogue and digital television as a prelude to the eventual replacement of analogue.

The key legislation was enacted in 1998 and 2000. With hindsight, government got a number of things right at the outset. The allocation of a full 7 MHz channel, heavily criticised at the time, helped secure the buy-in of the existing networks and, ultimately, viewers as well; a regional equalisation plan, government-funded to the tune of $260 million kick-started the rapid digitisation of smaller regional commercial TV services. Finally, the government mandated a same coverage requirement and made provision for the switch-off and return of the analogue TV channels—both measures with at least the potential to send a powerful message to householders about the need to upgrade.

Unsurprisingly, the government also got some things wrong. It initially restricted broadcasters to simulcasting their existing analogue TV offering, a concession to critics of the 7 MHz channel deal that reduced the incentive of both broadcasters and viewers to invest in digital TV. A second false step was the provision for licences for ‘datacasting’. In addition to permitting simulcasting by all existing services, we found we were able to plan two or more additional, 7 MHz digital TV channels in all areas. We will never know how these channels might have been used in a free market, because tight restrictions on datacasting content, intended to uphold the moratorium on more than three commercial TV services per market, ensured there was never any serious demand for the channels. But for reasons I will come to, this looks with hindsight like the best possible outcome.

Phase 2 (2001–2007) was a period of consolidation and learning from experience. Digital television was switched on in most major markets and the government reviewed and adjusted the regulatory settings where appropriate to increase take-up, notably allowing the inclusion of standard definition multi-channels. Together with new video displays coming onto the market that looked best with digital, households rapidly converted without even needing to know they were doing it.

It was only during Phase 3 (from 2007) that the focus turned to how analogue television might be switched off. It was only at this stage—just in time for the first smartphone—that the nature of any digital dividend resulting from the return of so many television channels received detailed attention, and analogue switch-off came to be recognised as a means-to-an-end and not simply the goal in itself. In particular, the government quickly realised that there might be better uses for the freed-up spectrum than five more datacasting licences at every site, and that by restacking the digital TV channels remaining after analogue closure, a large, contiguous block of valuable UHF spectrum could be freed up, harmonised with emerging mobile broadband allocations in Regions 2 and 3. The rest is history, although not before the commitment of many hundreds of millions more taxpayer dollars on publicity campaigns and call centres, means-tested assistance for householders to convert, compensation of broadcasters for the costs of retuning their transmitters, equalisation of TV services across all markets, the VAST satellite service for viewers beyond the digital ‘cliff’ and much more besides. A total of $2.4bn, from Phase 1 to the present day.

Some lessons

I learned a few things over this period, not least, what it is like to stand between the Department of Treasury and $3bn. But it taught me a few things, too, about spectrum re-farming more generally.

For example, the process shows how important it is, where spectrum use is concerned, for a medium-sized open trading economy not to peddle too far ahead of the international ‘peloton’. Hesitant and iterative approaches are going to beat long-term visionary plans every time. Humans love a good vision, so it’s easy to mock the government prior to 2007 for having no clear idea, beyond a saving in TV transmission costs, for why it wanted to turn off the analogue TV. But such evidence as exists suggests that if we had formulated such a vision significantly before 2007, it would have been wrong.

I will give one example only—in 2000, the Productivity Commission examined the whole question. It would be nice to report that our top economists noticed the evidence, already extant, of the emerging US 700 MHz ‘digital dividend,’ and said, hey, government, after you turn off analogue, why don’t you re-stack your digital TV and share out the spectrum between broadcasting and wireless broadband use cases according to need? But no, the Commission recommended more television. Much more television.

Its magic bullet idea was that existing broadcasters’ spectrum holdings should be converted into tradable spectrum licences. A broadcaster would be able to sell its spectrum while retaining its broadcasting content licence—for example, if it found a more spectrum-efficient way of delivering its services. It also called for:

- unfettered competition from new market entrants using any additional TV channels available during the simulcasting period; and

- processes to accelerate the supply of additional digital channels as clearance of analogue services proceeded.

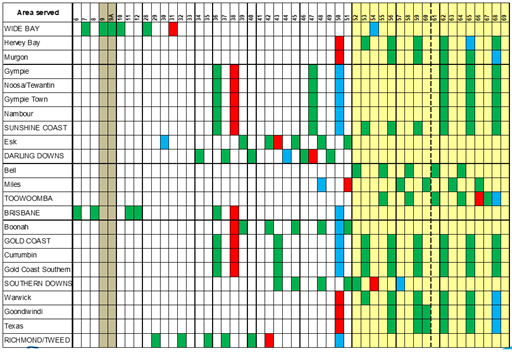

If we dodged a single bullet in this whole process, it was the government’s good fortune in failing to sell the datacasting channels. It left us free after 2007 to roll those unsold channels into what was arguably an optimal division between broadcasting and telecommunications use, with a border at 698 MHz (permitting Australia to harmonise fully with the emerging Region 3 700 MHz broadband allocation) while still making provision for up to six TV services at each location. Had we allocated those datacasting licences for the proposed 15-year terms, more TV channels—seven or eight—would have been needed at each site, requiring painful trade-offs—either a much-shrunken 700 MHz digital dividend, and/or serious problems with achieving ‘same coverage’ of the old analogue services, resulting from squeezing seven or more TV services in at each site. And this is just if we had managed to sell the datacasting channels—adoption of the PC’s recommendations would have made things much worse. Offering the TV licences as fully-tradable spectrum licences, as the PC proposed, is very unlikely to have resulted in market negotiations alone delivering the 700 MHz digital dividend, quite simply because there would have been too many independent actors involved on both sides of the trade—as the following diagrams show. The mobile networks would have been negotiating to achieve this outcome Australia-wide:

…With a bunch of broadcasters whose existing holdings, in the SE Queensland regional alone, would have looked like this:

Broadcasting futures

Having yielded one digital dividend, we have a ready-made recipe for yielding another.

So, let’s take a look in the pantry and see if we might have all the ingredients for a future, second digital dividend.

We do have a choice of more efficient standards.

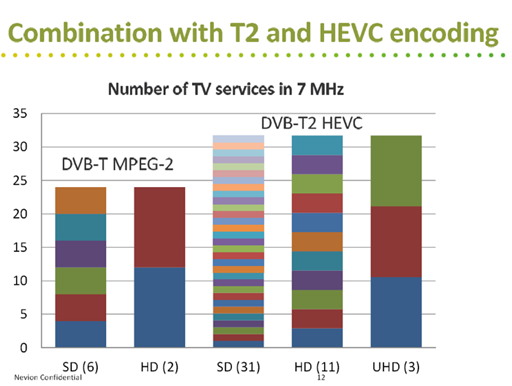

The DVB-T/MPEG2 standards underpinning digital TV in Australia are old; globally there are several contenting TV standards families to choose from—Bridget Fair yesterday quite rightly drew attention to the potential choice of ATSC, the American standard—but to keep things simple, if broadcasters used the DVB-T2/HEVC successors of today’s standards, which they have commenced trialling, they could get roughly five times as much television down a single 7 MHz channel as today—many, many more standard definition channels; or several more high definition (HD) channels; or, as claimed here, three Ultra-High Definition (UHD) channels.

We might also have a bit of scope to use more efficient standards to require fewer of those 7 MHz TV channels at each location, at least longer-term. In fact, we already have a potential seller of TV channels—the Australian Government, which uses or warehouses three out of the six, 7 MHz TV channels at every site, and drops occasional hints that it would like to sell at least two of those channels someday—the mostly unused ‘sixth’ channel, and also one or other of the two channels that are currently required for ABC and SBS services at each site. If we could only move ABC and SBS—and their entire audience, of course—to a five times more efficient standard, consolidation of national broadcasters onto a single multiplex would become a no-brainer.

So, we have a better standard and a possible seller of some of the current TV channels, but migration to DVB-T2 would be extremely expensive, even putting aside for one moment that penetration of DVB-T2 receivers into Australia’s eight million households is probably quite low. Simulcasting in DVB-T2 and other contemporary TV transmission standards will require its own channel and transmission network separate from the existing DVB-T infrastructure—initially a single channel’s worth could be provided using the vacant, sixth TV channel in all areas. The whole expense of migrating ABC and SBS transmissions to the new standard would fall to the Federal Government. The commercial broadcasters would also presumably face very significant expenses—remember that sum of $260m, which the federal government contributed towards the costs of regional commercial TV in moving to simulcast in digital.

Is the investment likely to be worth it to the TV industry and the Federal Government? During the 1990s, broadcasters were motivated to embrace digital TV by the emerging threat of pay television. Digitisation ensured they were able to match or better the pay TV proposition on picture quality for many years. It is an interesting question what they would be buying this time by further investment in their legacy broadcasting transmission platform.

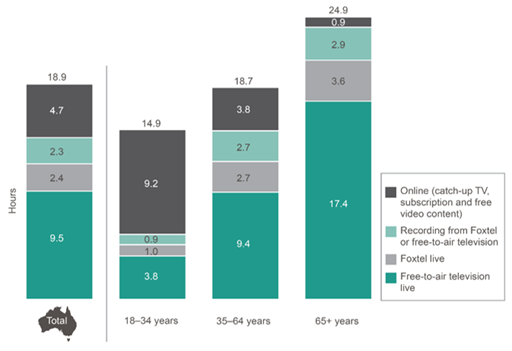

While free-to-air TV remains the dominant source of the video content Australians consume, this slide – sourced from ACMA research - suggests younger Australians have largely abandoned video content delivered via broadcasting in favour of internet-delivered content (free-to-air has a slice of this market, too—catch-up TV). So, if you are a broadcaster, do you invest in the broadcasting transmission platform, to try to keep more of those older eyeballs for longer? Or do you invest in growing your slice of the burgeoning internet market? Can you do both? The TV industry, in conjunction with infrastructure providers BAI and TXA, has this year begun significant trialling and testing of DVB-T2 in Australian conditions. But whether there is a business case for the full technical standards migration of TV after a period of simulcasting remains unclear.

If it turns out there isn’t a TV business case for upgrading the transmission platform, is there a broadband wireless business case? Here we are fortunate in having an international model already—the US, which devised an almost unbelievably sophisticated, two-sided auction to create and license a new wireless broadband allocation in 600 MHz while compensating broadcasters for migrating out of it.

There is currently little global interest in a 600 MHz broadband allocation—in fact, right now, ‘over 1 GHz’ is looking like the new ‘sub-1 GHz’—but North America is going its own way on this one and it is of some interest to see what they’re doing, noting that the original US 700 MHz digital dividend did anticipate, and possibly influence, the ultimate boundaries of the APT 700 MHz allocation, on which Australia’s digital dividend is based.

As you can see, the US 600 MHz allocation lines up quite neatly with two of the five, six-channel ‘blocks’ of TV spectrum that are the ‘tiles’ out of which we have built the TV band plan. If Australia ever decided to adopt a second digital dividend based on the US 600 MHz dividend, it could do so by reducing the number of 7 MHz TV channels at each location to four or, ideally, three channels, and then doing a re-stack.

Maybe, sometime in the future, there’ll be a case for our very own ‘two-sided auction’ here, to apply the rising value of a 600 MHz wireless broadband allocation to the costs of upgrading TV standards. But at the moment, there is little global pressure for further sub-1 GHz wireless broadband allocations. And Australia already has a significant block—2 x 15 MHz—of sub-1 GHz spectrum awaiting price-based allocation in the 850 MHz expansion band, noting some of this might alternatively be required for Public Safety Mobile Broadband. We could also make better use of the existing 900 MHz wireless broadband allocation, by reconfiguring it to 2 x 5 MHz pairs and downshifting the existing 850 MHz spectrum licences.

So, I wouldn’t be organising any two-sided auctions just yet, and the question of the value and utility of upgrading TV technical standards remains one for the TV industry (including the two government-funded networks) for the time being.

My takeaway message is that the ‘digital dividend recipe’ provides one model for future evolution of the TV bands, but, at least for the next few years, it is likely to be a very expensive one. It will critically depend on the emergence of business cases from either or both of the TV industry—including the government-funded parts of that industry—and the wireless broadband industry, and the shape of it will depend on what those business cases are.

Politics, and the virtues of civility

As this is my farewell address to RadComms in my present role, I’d like to finish up with some personal messages. In all the talk about departures yesterday, we didn’t mention that Alan Major will be returning to ACMA’s spectrum team in mid-November. After a longish stint managing our corporate IT function, Allan will be filling Mark Loney’s shoes as the head of our Operations, Services and Technology team. Please welcome Allan, who, as many of you will know, previously managed this team and brings considerable knowledge and experience to the role.

I’d also like to welcome Cathy Rainsford, the Department’s senior official on spectrum policy, into her new role as head of the Australian delegation to WRC along with other international forums. The change marks the successful implementation of Recommendation 4 of the ACMA Review, and I would like to pay tribute to the collegiate and professional way this transition has been handled by staff on both sides. My particular thanks go to ACMA’s Executive Manager of Spectrum Engineering and Planning, Chris Hose, and to Cathy herself, for their dedicated focus on Australia’s preparations for WRC-19. This bodes well for the successful leadership of our work in Sharm-el Sheik next year.

I’d like to conclude with a message about civility. At the start I compared spectrum management to town planning, but unlike real estate, you can’t see and touch spectrum bands. We need engineers or scientists to tell us what their relevant properties are, and that immediately creates a problem of communication. One of my unhappiest digital dividend experiences was being in the room when a departmental secretary first realised that the amount of TV spectrum you had to clear for your ‘digital dividend’ - for example, 18 x 7 MHz channels, or 126 MHz - was quite different from the amount of spectrum this yielded for mobile broadband, once regional harmonisation and the need for guard bands and a mid-band gap were accounted for. The cause of this revelation was the quite innocent remark of an engineer, for whom it was obvious, and who hadn’t been asked that specific question before.

This problem of invisibility and technical complexity means that the best spectrum policy requires collaboration between widely different disciplines—spectrum engineers, economists, policy and political advisors, lawyers and accountants. And as my departmental career-limiting move shows, communication at the boundaries between these disciplines can be inefficient. Comically inefficient. Osmotic, even.

So, the quality of spectrum policy work really depends on the quality of human interactions between groups of people with very different training and backgrounds. Civility and respectful communication are critical to the quality of these interactions. Less interpersonal friction actually promotes vigorous debate and the contest of ideas. I was present at the WRC Preparatory Group meeting earlier this week when Cathy Rainford spoke up strongly for greater civility, amongst other things, in our dealings with each other in the preparations for WRC. I endorse her remarks. Civility isn’t something that’s just nice to have, it should be seen as a precondition. And really, how hard is it? It starts with good manners. We don’t have to make things personal. And the search for win-win compromises requires that we try not to adopt polarising positions, or the reflex tagging of compromise proposals as sell-outs to the other side.

The digital dividend shows that a complex microeconomic reform in this field, one that affected every household in the country, can be undertaken with a high degree of bipartisanship, and indeed, steered to a satisfactory outcome by alternating Coalition and Labor governments. Spectrum policy is rife with politics, just like everything else governments do, but it’s been generally seen as too dry for partisan debate in the media. I hope you all appreciate what a blessing that is for your industries and this country, and try to keep it that way.

It has been a privilege and a pleasure to work as part of this community of expertise, and I wish you all the very best with your future endeavours.

Thank you.